When it comes to selling things and getting people to pay you, the importance of understanding the psychology of how and why people buy can never be overstated.

Getting people to pay for your products and services doesn’t just end with with getting a payment processor; in fact, the best payment processor can’t help with this.

Also, there’s a limit to how much marketing can do to help you close the sale. However, by understanding the psychology of how customers buy and by tweaking your sales message to this effect, you’ll be able to get a lot more people to pay for your services. This article will be sharing 3 psychological studies on payment and pricing as well as how your business can benefit from the findings of these studies.

1. The Economist Pricing Study and the “Decoy Effect”

“In marketing, the decoy effect (or asymmetric dominance effect) is the phenomenon whereby consumers will tend to have a specific change in preference between two options when also presented with a third option that is asymmetrically dominated” – Wikipedia

In more simple terms, the decoy effect is the process of introducing a pricing you don’t really want people to consider so that it can influence people’s decision to consider the main pricing option you want to attract attention to.

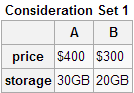

To put this in perspective, we’ll also use an example from Wikipedia on the sales of MP3 players. The screenshot below shows what the main pricing for the MP3 players you really want to sell is:

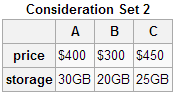

This screenshot, however, shows what pricing looks like after a new “decoy pricing” option is introduced.

You’ll notice from the two pricing options included that the main product they’re trying to draw attention to is product A, the 30GB $400 MP3 player.

You’ll notice from the two pricing options included that the main product they’re trying to draw attention to is product A, the 30GB $400 MP3 player.

Here’s how this works: Initially, with the first pricing option, potential customers might decide to go for the cheaper 20GB MP3 player because it’s cheaper and they “don’t really need more space!” However, with the introduction of product C, in the second consideration set, that costs $450 for a 25GB MP3 player buyers will be inclined to consider product A; the main product they want people to buy.

In other words, with the decoy pricing introduced most people will now see product A as a bargain and naturally favor it.

The effectiveness of this was proven by a study conducted by The Economist, described in Dan Ariely’s Predictably Irrational. At the time this study was conducted, the initial pricing used was:

- A web-only subscription for $59

- A print-only subscription for $125

However, as expected, more people favored the web-only subscription. In an attempt to get people to consider the more expensive subscription, an additional option was introduced that made the new pricing look like this:

- A web-only subscription for $59

- A print-only subscription for $125

- A web + print subscription for $125

To test the effectiveness of the decoy effect with this pricing, Dan Ariely conducted a study with 100 MIT students to determine which option will be the favorite. 84% chose the web + print option while 16% chose the web-only option. Nobody chose the print-only option.

In this case, the middle option was the decoy pricing intentionally designed to get people to pay more attention to the web + print subscription which is a bargain compared to the rest.

2. The Jam Study and How by Too Many Options Can Make You Lose Sales

As is obvious from the “Decoy Effect” explained above, introducing “controlled pricing options” can influence their decision to select the pricing you want them to consider; however, how much is too much?

In closing deals, giving people too many options will actually ensure that they go for the best option they can think of: NO OPTION.

This was proven in a 1995 jam study conducted by Sheena Iyengar; in a California gourmet market, Iyengar and her assistants set up a booth of samples of Wilkin & Sons jams. Customers were then allowed to taste from a set of 24 jams and a set of 6 jams before deciding from which to buy; every few hours, the jam groups were rotated so that different customers are able to see different options.

As expected, more people were attracted to the assortment of 24 jams while fewer people were attracted to the group of 6 jams; surprisingly, though, 30 percent of those who were attracted to the group of 6 jams decided to buy jam while only 3 percent from the larger group exposed to the group of 24 jams bought jam.

In other words, while having a lot of pricing options can attract people to your product and make them consider it, it’ll do just that; make them “consider it.” When too many choices are presented we’re programmed to default to no choice.

Ensure you offer very few pricing options that you control and more people will buy; have too many options and nobody will buy.

3. Price Anchoring Can Help Double the Value of Your Product

When you really have to sell a product for $200 and you think people will think it’s not even worth $50, leveraging the principles behind anchoring can help.

Whenever we want to buy something, we already have a preconceived idea of how much that thing is worth and our idea of the worth of something is often influenced by a lot of factors; this includes the industry, past experiences etc. However, how do you get people to pay more when they think your product is worth less? Anchoring!

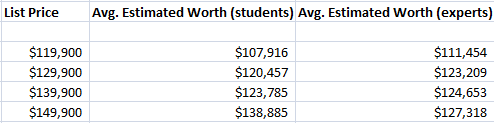

The effect of anchoring was demonstrated by William Poundstone in his book, Priceless. Poundstone described an experiment on real estate prices; experts and undergraduate students were invited to appraise a home for sale; the subjects were then given all necessary information that will help them make the decision to appraise the house, including how much the seller lists the house.

The subjects were then divided into 4 groups and each group was given a different list price for the same house. The subjects were then asked to appraise the same house to determine how much it’s worth. Here are the 4 pricing information provided to the subjects as well as how much they thought the house was worth:

As you’ll see from the above table, the subjects were more likely to estimate the house to worth a lot more when given a higher list price. That’s the anchoring effect in place.

So next time you really want to sell a product for $200, tell people it’s worth $500.